How Has Car Glass Evolved Over Time?

Nowadays it is easy to take for granted the array of modern conveniences we can expect to find in our cars. Sure, each passing year seems to bring with it some sort of technological advancement that would previously be considered as the stuff of science fiction.. But long before the days of on-board computers and advanced driver assistance systems, boffins all over the world were making advancements that still shape the world of motoring today. Unsurprisingly, here at Autoglass® we have a particular interest in how the glass we find in our modern cars has advanced since the inception of the automobile. With that in mind, we thought it might be interesting and informative to dive into the fascinating story of how car glass has developed from the very first automobiles all the way up to what we find in cars rolling off production lines today.

Early Car Glass

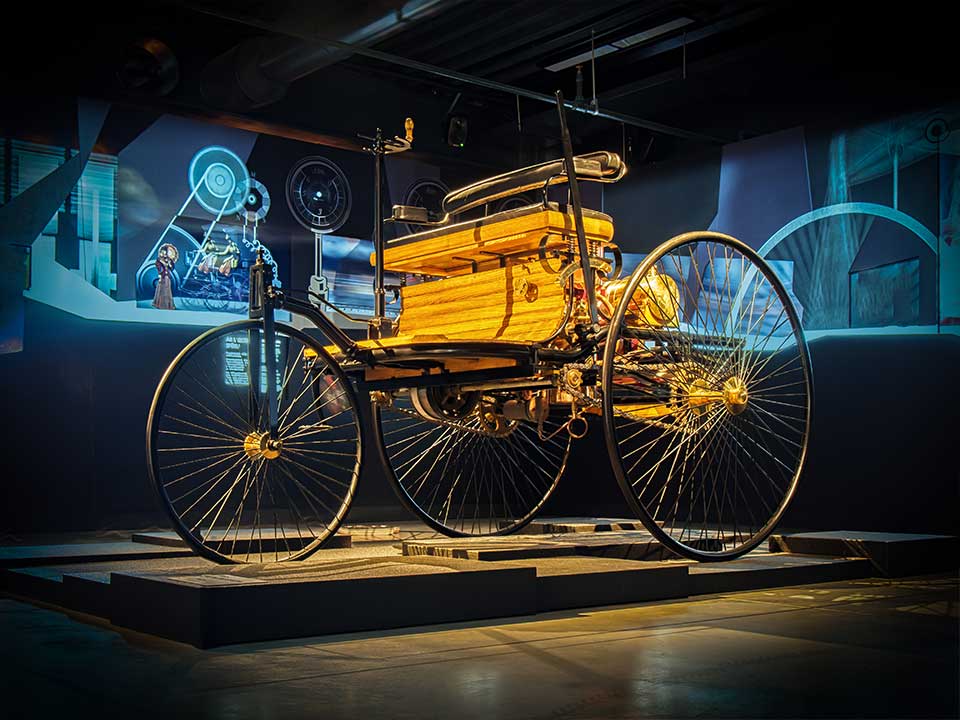

The first automobile was introduced in 1886 by Carl Benz but it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that cars became recognised as a viable form of transportation. These first cars had some resemblance to what we see today, not least of all in how they employed glass. For instance, at their first introduction, windscreens were considered an optional, luxury extra. Additionally, the windscreens themselves were very different from what we have today. These earliest windscreens were just a simple thin pane of glass designed to be folded away when not in use.

Ever wonder how an airbag works? >>

A Major Discovery – Shatterproof Glass

The earlier windscreens only really served to deflect wind away from the occupants of the car. That is to say that they did very little to protect passengers from stones, debris or other hazards. That all changed in 1903 when French Chemist Edouar Benedictus accidentally discovered shatterproof glass. Benedictus was working in his laboratory when he dropped a flask coated in a dried collodion film and realised that the flask did not shatter into pieces on the ground, but instead stayed together with a spider-web-like crack running through the glass.

Benedictus soon realised his breakthrough could be a new way to protect drivers by making windscreens from polymer-coated glass that resisted shattering and stayed in the windscreen frame in the event of an accident. After a few years of development, he patented a safety-glass laminate composed of two layers of plate glass with a layer of cellulose sandwiched in between.

Polyvinyl Butyral becomes the standard

By the 1920’s, automotive manufacturers started using shatterproof safety glass and laminated glass in windscreens. From this point the practice became commonplace and a number of companies made laminated glass for windscreens and other applications, but early versions of this safety glass often became discoloured as the inner layer of plastic deteriorated over time. Glass companies and carmakers found that a compound known as Polyvinyl Butyral (PVB) was more resistant to discolouration and over the course of the next decade a number of companies began using PVB to laminate their windscreens. As a result of worldwide safety regulations implemented since the 1960s, laminated windscreens are now standard everywhere, and although various materials have been trialed, PVB remains the most commonly employed across the automotive glass industry.

To make PVB laminated windscreens, manufacturers cut sheets of soda-lime glass, approximately 2.5 mm thick, and shape them in a furnace to fit the specific curvature of the car’s windscreen frame. Then, the glass and PVB film is fused together in a piping hot, specially pressurised unit known as the autoclave. The procedure causes the PVB to thoroughly soak the glass surface and drive hydrogen bonding between the layers, further strengthening the laminate. The result is a tightly bonded, perfectly transparent layer of car glass that resists shattering in the event of an accident.

What does your car colour say about you? >>

The Birth of the Windscreen Wiper

As we know, the earliest windscreens were designed to be neatly folded away once they became too dirty to serve their purpose. As automotive transportation became increasingly commonplace, a solution was needed to keep these windscreens clean and transparent. A solution was discovered by Mary Anderson when she arrived at what we now know as the Windscreen Wiper. Prior to her discovery and patent for what she called at the time “a window cleaning device” Mary Anderson was a successful real estate developer from Alabama. She arrived at a prototype consisting of spring-loaded wooden wipers with rubber blades. These wipers were then attached to a lever inside the vehicle that the driver could pull to wipe away snow, rain, and whatever other hazards they may encounter on their travels.

Laminated and Float Glass – a New Frontier in Safety

Following on from the integration of safety glass into automobiles, the march towards safer motoring continued. The subsequent decades saw the development of laminated and tempered safety glass. Laminated glass involves bonding a plastic layer between two sheets of glass. In the event of an impact this plastic layer holds the glass together, preventing it from shattering into numerous dangerous fragments.

In 1959, the glass production world was revolutionised once again with the introduction of the Pilkington Process, also known as the “float glass”. This process essentially involves having the molten glass evenly poured over a liquid metal bath, usually tin, to provide even thickness and a consistently ultra-smooth surface.

The latest developments in vehicle glass has seen windscreens increasing in size in order to accommodate newer, more aerodynamic designs. As one might expect, the use of glass is increasing relative to these changes in automobile aesthetics. Rather than sticking with conventional tempering methods, many manufacturers are switching to a chemical-based tempering process to strengthen the glass. On a similar note, manufacturers are also making glass thinner, which in turn makes vehicles more fuel-efficient. To avoid having to use larger air conditioning systems, new glass compositions, coated glasses, and aftermarket films are also being considered. In coming years, motorists may even expect to see angle-selective glazings that reject high-angle sun, and optical switching films.

Tips for Avoiding Windscreen Damage While Driving >>

Heated Glass

When we think of modern conveniences associated with windscreens – heated glass has to be one of the first features that jumps to mind. Up until recently, Windscreen glass has traditionally been heated through radiation. Unfortunately this process has been known to create uneven temperatures along the structure because certain portions, such as screen-printed areas, more easily absorb radiated heat than clear glass.

In recent years, a convection style has been adopted to heat glass, meaning the glass can now heat more efficiently and evenly. This lack of temperature discrepancies that result from convection heating also helps prevent the glass from breaking during the heating process, and it also prevents burn lines from appearing on your car glass.

Smart Windscreens – The Future of Car Glass

The final frontier in windscreens is undoubtedly smart glass or “Electrochromic glass”. Electrochromic glass allows drivers to choose to tint their glass and select the amount of light that is filtered through the glass. Other smart glass features include displays on the side mirrors that warn drivers of the movements of other road users. On a similar note, digital displays can also project important messages directly onto the windshield, allowing drivers to continue driving safely and access controls quickly and easily should something unexpected happen.

So there you have it; our whistle stop tour of the past, present and future of automotive glass! We hope this brief guide has cleared things up (pun intended!) and don’t forget to check the Autoglass® blog again soon for more explainers, tips and guides for all things motoring.

Book an appointment now

For a quick and easy way to make an appointment book online now.